Juid groaned in discontent—a lengthy, pained groan of a man who had been unappreciatively and prematurely roused from slumber by circumstances which couldn’t possibly have been more important than a solid night’s sleep. The alarms, having been designed to alert the population of a potentially lethal scenario, had become so commonplace that they existed now as mere background noise to the cacaphonic soundtrack of Juid’s life. And Juid, like everyone he knew, was station-born, and so knew nothing of a life devoid of such constant threat. But his ever-adaptable human mind had long since accepted the dangers as inevitabilities—constants of his physical environment—which no longer invoked a survival stress reaction.

Management disagreed with this blasé assessment, however. Juid’s superior, indignant at his delayed response, opened the hatch to his quarters without announcement or permission, cursing as the eternally sticky handle caused a fumbled entrance and a painful cranial impact upon the bulkhead—justice served to a courtesy violation. Juid failed to suppress a grin, despite his state of sleep-depravity. Even through the chronic fatigue, and regardless of that fact that he was being summoned in person, he had already surmised that the problem was adequately severe, independent of the alarms (which were still screeching, Juid noted). His most astute conclusion was formulated upon the observation of extremely reduced gravity, at once apparent as Juid rose from the prone position, which in turn meant that the station’s rotational velocity had been reduced, which could only therefore mean that it had suffered an explosive decompression somewhere—or had experienced a collision with some foreign object (or both), which would also likely mean decompression. The causality chain was gradually coalescing in Juid’s fatigue-clouded mind. Either way, it meant that there was hull damage and needlessly wasted atmosphere. That would only lead to further resource rationing. Juid knew who would feel the pinch. It was a series of events that would conclude in no positive outcome. Juid groaned again, this time a groan of slightly shorter duration than previously, now triggered by emotional displeasure rather than from physical discomfort.

“Get dressed. 50-39-56.” His manager left, rubbing his head at the site of impact. He was not in good humor today, although the blow to the head had likely evaporated any that would have been there to begin with at this hour. He also looked less fat in reduced-G, Juid mused as he left (quite a feat to become fat upon standard rations).

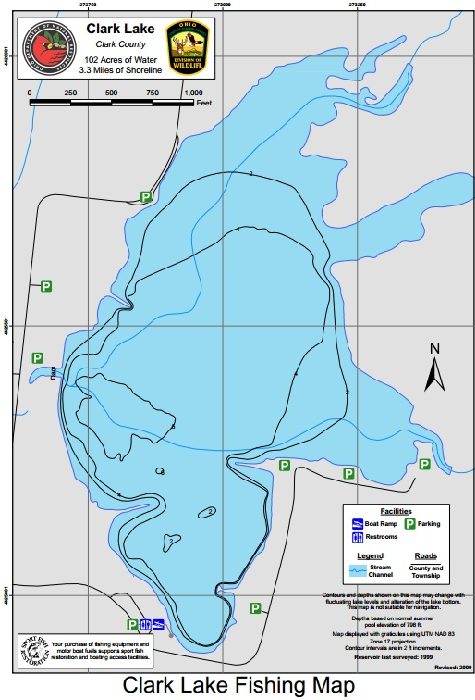

The station was mapped on a coordinate system. This was practical as it was rotationally symmetric, so the X-Y-Z, 3-dimensional field of reference applied seamlessly, measured from the ring’s center of mass (which was not within the station itself, as such a location would have no simulated gravity). Of course, the interior of the station was not nearly so homogenous as the coordinate system would have implied, being restricted only by rotational symmetry of mass. A more practical system would have included numerical designations at corridor junctions, in order to pinpoint impacted sections and more efficiently direct an individual through the maze. And it once did. Centuries of groping hands could never polish away the numbered plates bolted at every door, airlock, and intersection. But such information was lost to time, and unnecessary these days. Juid could navigate the station blind, as could everyone. It was the only home they had ever known, and they had had their entire childhood with which to imprint the spacial references to memory. Juid knew exactly where to go and how to get there, and only required those three simple numbers to tell him.

Juid opened the locker to his vacuum suit (a most utilitarian receptacle), upon which it gracefully fell in the low gravity to the floor in a disheveled heap. Juid had hung it up properly of course, but the low-G had apparently caused it to dislodge from its moorings. He picked it up and cautiously sniffed the collar, the way one does with full knowledge of the olfactory violation to come, and upon receiving the anticipated sensation, recoiled slightly at the familiar stench of his own concentrated body odor. It was his odor, yes, having finally triumphed over the suit’s prior owner’s, but still, he didn’t relish basting in it for extended periods. He gagged. Water rations always precluded the laundering of any exo-wear, forcing suit owners to make due with a myriad of toxic solvents instead, trading the discomfort of solidified oil for the ultimate health costs of long-term carcinogen exposure. Juid was certainly no exception. He wiped the inside with an industrial de-greaser and winced at the chemical fumes. Then, with his eyes properly burning and the suit’s lining mildly caustic to the touch, Juid donned the vacuum gear.

The suit was bulky, but was designed for interior, not external, maintenance. This meant that it had to fit through narrow access hatches. So, it wasn’t a giant fabric bubble, as the first suits were, but rather a compacted body suit, still thick with insulation and tear-resistant fiber, but relatively mobile. It was solid technology, relying primarily on physical pressure, rather than atmospheric, and remarkably still intact from Before—which was why Juid was not its first owner, nor would he be the last. Juid grabbed the helmet and exited his quarters. He would wait until the last minute to seal himself completely, thus minimizing the time he would spend inhaling the nauseating combination of aforementioned body odor and pungent chemicals.

In the hallway, business carried on as usual, as was to be expected. Pending death was no reason to cancel daily plans, and like Juid, the station’s populace had grown to become generally unresponsive to the frequent alarms. The only difference was that today people were galloping down the corridors like wild beasts (not that Juid had ever seen any such beast in person) because of the reduced gravity—an unintentionally comical sight. The few children on board could be heard squealing with delight as they relished the opportunity to literally bounce off the walls, oblivious to the severity of the situation. Juid had to dodge more than a couple. But, at least it made moving in the vacuum suit easier.

In short order, Juid arrived at his destination. As a general policy, bulkhead doors were to remain closed at all times. This was for obvious reasons, case in point, although the greater threat historically had been fire, not decompression. It was far more likely than an electrical malfunction in a high-oxygen environment would trigger disaster, rather than a catastrophic hull failure. But regardless the original reason, the present circumstances benefited from this practice. Although, had no policy been in effect, it would have still been de facto. All doors opened against the rotational force of the station, and so remained closed if not by policy, then by physics alone. They were originally powered pneumatically, saving the operator some effort, and although the majority of those pressure systems had since failed, the doors were still counter-balanced. A mere toddler could open them if so inclined. And even in sections where the weighted pullies too had failed, the doors themselves remained a modest 30 kilos under standard gravity. It didn’t require much material to hold back low atmosphere.

However, it was generally not possible to open a door against the pressure differential of 0.6 kPa. This meant that an airlock would need to be jury-rigged from the series of hatches. The improvisation involved gathering all maintenance personnel, cordoning off the hallway between the door to open and the next bulkhead door, placing a notice on the outside of this far door warning of deadly consequences (not that any casual passersby would be able to open it anyway), running a compressor to reduce the ambient pressure of this now dead space, then forcing the door with a most elegant too—a large crowbar (or in this case, a 2-meter bar of sharpened steel). The purge of this small cavity of air at reduced pressure was rarely more than a strong gust, and then behold! Access to the compromised structure. And the ventilation ducts were even valves, designed to close against vacuum. The station was a marvel of old-style engineering—mechanical failsafes independent of any electrical control systems. They were with certainty the only reason anyone could still live here at all. Computer systems would go offline through data corruption, and as their programming languages became lost to time as new generations failed to grasp their context, but the tactile world of mechanical engineering was rooted in universal perception.

Following the aforementioned procedure, Juid and crew examined the breach. In short—it was large. A small breach didn’t cause decompression, just a gradual leak. The station was riddled with gradual leaks, often plugged with nothing more than fabric adhesive. This job, however, required welding. Welding used valuable resources, so before repair work was authorized, scans of the damage were forwarded to management for approval. The photograph crew did just this. And then they waited.

In Juid’s experience, this was a worthy repair. Repairs that were not cost effective or of minimal impact simply remained sealed off—bulkhead doors closed eternally and forgotten to time, or until the next trade pod (if it contained sufficient materiel and an appropriate deal could be struck). But in this instance, the affected junction was heavily trafficked, yet the damage was not sufficiently large enough to compromise the hull’s greater integrity. This scenario belied a much larger problem, however. This particular type of damage was becoming increasingly common, and management was only denying the long-term implications. These exercises were simply not sustainable with the dwindling access to supplies. But that didn’t concern Juid at the moment either.

The station, aptly named “Lagrange 1”, resided at Lagrange point 1, which is to say it was locked into a comfortable position between the planet below, and its natural moon above…so to speak. The benefit to this arrangement was its permanence, and had been chosen with intent by the station’s original designers. The station would never suffer the fiery cataclysm of a retrograde orbit. It was, as all things within it, timeless in existence yet terminally ill. It would always remain here, even after it was no longer capable of supporting life, ultimately finding its fate as a fragmented mass of floating debris, sealed in relative position until the system’s star transitioned into a red giant.

Such had been the fate of Lagrange 4. Its former occupants had asphyxiated in the emptiness of space, presumably after their station had suffered an impact too severe to be recoverable. Or perhaps they had run out of compressed air, or scrubbers, or the power grid had failed. It was impossible to establish a timeline of events, or isolate a probable cause from the myriad of problems which may have arose, as any evidence to solve the mystery had gradually eroded from the constant barrage of orbiting particulates once no one was left to make the repairs.

Thousands of kilometers away, the inhabitants of Lagrange 3 had, out of their own survival necessity, sent an exploratory salvage team to Lagrange 4’s location after rediscovering its existence in their archives, and ultimately the location of all the Lagrange stations. This was centuries ago, and had marked the beginning of the earliest trade caravans. L4 was far closer to L1 than L3, but by the time all Lagrange stations had established communication channels and were in possession of operational shuttles, L3 already had a salvage monopoly in place, and since L3 was running the risks of salvage, and had formed the basis of the original trade systems, all other stations were reluctant to disrupt the balance and potentially compromise their already tenuous mercantile system. Unfortunately, this also meant that one station controlled the only source of materiel needed for repairs and equipment replacements. Increasingly, the cost of said materials made these repairs prohibitively expensive.

The tear in the hull, which Juid had now patched with an aluminum plate and sealed with a thermolytic chemical reaction, had cost them collectively a week’s worth or water rations. The giant spaceburg, which dominated half the station’s total mass, had been hauled in from the outer system during the stations’ construction, and served as the primary source of propellant, gasses (notably oxygen), hydration, and general sanitation. All the Lagrange stations had their own supply (excluding the former L4, who’s was notably—and suspiciously—absent), and it served as the only practical means of currency. But while their sheer size seemed eternal, like the salvage shortage, it was a dwindling supply.

It was a point that Juid was tired of arguing. Reporting concerns directly to senior management was highly irregular, and so Juid was forced to try to reason with his permanently apathetic direct manager. His manager surmised, correctly, that he would be long-dead before water shortages and escalating costs of supplies would spiral completely out of control, and while this attitude presented a direct contradiction to why management was so frugal with the supply, the mere fact that the system was working at all was sufficient reason to maintain indifference. Therefore, he was only concerned with his own immediate wellbeing, which primarily involved his tireless pursuit of any number of the diminishing population of vastly outnumbered women on station.

This last thought was bouncing through Juid’s mind as the radio clicked to life with his boss’ consent for the repair order. He enjoyed a mutual moment of amusement with his colleagues who all noted that they hadn’t waiting for permission.

They waited a bit so as to maintain the veneer of subordinate obedience, then Juid sent over a radio communication. “The repair’s done. We’re ready for a test compression, unless you want to check the work personally.” Final signoff always fell to him, officially, even if he knew little of grunt work himself, or cared at all.

“No need, go ahead and pressurize.” Juid may have been mistaken, but he could have sworn he had heard yawning in that response.

Whatever, he never had been a competent welder to begin with—part of his quick advancement no doubt (Juid’s turn to feel mild indifference). He walked to the nearest ventilation duct and forced the manual release. Air hissed its way through, slowly as it always did (another mechanically-engineered safety). Had he not been wearing his vacuum suit, Juid would have experienced the blast of stench firsthand from the accumulated dust which only now, after being subjected to a significantly faster stream of air, was freed from its duct purgatory. The crew would have to wait. Juid checked his pressure readings, noted the time, and made an estimate. It would be an hour at least. He glanced to one of his colleagues, who was doing a similar check. Through their gold-laminated faceplates they met an imaginary gaze, and the man shrugged. They both knew, and there was nothing else to do in the meantime.

“Might as well tell the engine crew to get started, Bob.” The status of the air pressure in this one junction wouldn’t impact the process of restoring the station’s rotational velocity. And regardless, this crew’s job was done.

“Yeah, okay.” Another yawn—this time definitive. Asshole.

A few minutes passed and then a sudden lurch shook the station. Equatorial thrusters were venting water vapor. Though he could no longer see outside, Juid knew that a month’s supply was being dumped into nothingness. Inwardly, he sighed. They would feel the pinch. He imagined as the station’s rotation spun the building cloud of ice crystals into a toroid.

Gradually, Juid’s feet grew heavy. The weariness of the job only now manifested with the return to normal gravity. But on the positive side, they would now all receive an ethanol ration, as was customary. Each repair job netted a little bonus, and Juid suspected that this was top management’s way of helping the proletariat forget the hard work, bad pay, and hazardous conditions (plus, giving people a depressant tended to quell their rebellious energy). Juid would have preferred an extra water ration, or a complementary suit cleaning, but at least he’d enjoy an evening of recreation. And in addition to the ethanol there was one more perk of the job. Tonight, management would send down some of the women for entertainment. It had been weeks since Juid had talked to one, probably just as long since he had even seen one, and there was always that small chance he could arrange for an official courtship. Hope was a great motivator.