As many from the older generation lament: they just don’t make ’em like they used to. Truth. There was indeed a point in American history when we actually had a proper manufacturing industry. And a core component of this industry was American steel. And in the height of steel’s influence, before petroleum-based plastics and outsourcing, things were created from metals whose only enemy would be rust and time, not wear and tear. Now these icons of the past stand as monuments to another era, seemingly so different from the one in which we live now.

Seeking these icons has become popular enough to warrant its own term: urban exploring. But I find that one doesn’t even have to put effort into it to net results. Sometimes by sheer chance the past will emerge, demanding that it not be forgotten.

Years ago when I had purchased my first iPhone, I would check Google maps (when this was the default map), passively exploring the green belts which stretch their way through developed metropolises. I would trace the routes digitally, musing on what lay within. In the building in which I worked, beyond the parking lot, one such belt resided. No label had been applied courtesy of the map, yet it delineated a zone between the building and the residential section of old post-war houses, presumably built in a time when the nearby factory (still in operation, though I have no idea what it produces) was likely a major factor in the area’s economy. Who knows? It might have been steel.

One day, as was all too frequent in those days, I was desperately seeking an escape from my job. The allure of this mystery zone tugged at my thoughts, and so I set off on a 15-minute excursion (the mandatory minimum break time required by law, so granted unto me by my employer). I trekked to the end of the parking lot and encountered the hedgerow–an unsurprisingly impassible barrier of invasive honeysuckle, bordering a drainage ditch. I decided to trace this line to the end of the lot, and there, just as it terminated into a chain link fence, it parted. The opening was the result of an old roadway, bridging the ditch and dead-ending into a single pole in the grass by the parking lot, obscured from view by the unruly foliage.

Naturally upon this discovery, I couldn’t not continue down the path, so like a suburban Livingstone I fearlessly marched through the vegetation. On the bridge I received a view of the drainage ditch, which from above now appeared to be the remnants of a natural waterway. Below, carp circled while ducks traversed the surface, bathing. It was an idyllic scene of natural serenity in a profane expanse of asphalt, but the road continued, so I pressed on.

After crossing the short bridge, the hedgerow on the far side too disappeared, giving way to a vast expanse of grass, interspersed with groups of trees. The grass, while not meticulously manicured, had still been maintained. It was knee-high, and resembled a prairie, mixed with thistle and clover. Bees merrily conducted their business in the blossoming grassland, and I wondered why this stretch had been mowed. The only clue to this mystery was a series of gas line utility marker poles, spaced regularly throughout the stretch.

The road bent around a tree grove and there I saw it: the remains of a park. A party gazebo stood, although made of wood, still without apparent structural damage; a set of swings, or what remained, as the swings and chains themselves had been removed; and a steel slide–no doubt anchored with concrete and too much trouble to remove. And running adjacent to the road was a 7-foot chain link fence, topped with barbed wire. Yet amusingly, more drainage pipes passed beneath the road, bypassing the fence with 4-foot diameter concrete tubes. I was happy to see that neighborhood children had discovered this, as a group was playing on the dilapidated remnants of the old playground. Why was this area fenced off? Why had it been closed? Had budget cuts doomed the park? The answer could have been deduced from a notice sign, but any explanation it may have offered had been covered in spray-paint. The children, blissfully unaware of liability, had ignored the notice and all that the fence implied.

Yesterday, we were in attendance at a family function, in a Knights of Columbus charter house. They were extended family on my in-laws’ side, so any common-ground conversational points were limited. For a moment’s reprieve, I stepped outside. The entrance was no sanctuary, as two people were engaged in phone conversations, so I began a walk to circumnavigate the building.

And there, in the back, out of time and place and seemingly forgotten, remained a steel slide. No other playground equipment remained–only this slide. I pondered its existence a moment as I had the park remnants behind work. Surely people know of it, because again the grass was mowed. Why is the grass always mowed?

My daughter, having been eating cake since we arrived at the party, and no doubt needing a break of her own from social over-stimulation, was elated when I mentioned the hidden slide to her. She gleefully skipped off to partake in this forgotten joy.

Why are these things forgotten and disused? In the post-war baby boom, did we have a greater need for them, now no longer after the generation aged? Like the Giving Tree, they sit, silently waiting to give again–any joy that they might still provide.

I took a photo, partly to see my own child enjoying the slide for its intended purpose, partly to prove that the permanence of these old icons was not without merit. Whatever its future fate, proof that the slide brought a child happiness one more time will remain now in the chronicles of family photos, possibly to outlive the steel itself.

–Simon

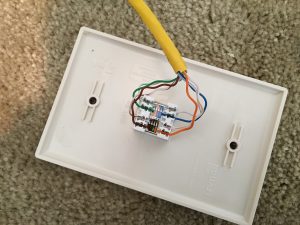

gathered around it and fighting. Now let’s compare that to, say, a water tower, where everyone in that same crowd gets their own spigot. Everyone attaches a hose, and everyone’s happy. This latter explanation is wired Ethernet.

gathered around it and fighting. Now let’s compare that to, say, a water tower, where everyone in that same crowd gets their own spigot. Everyone attaches a hose, and everyone’s happy. This latter explanation is wired Ethernet.